Mailstrom

Fights about mechanization, automation, and collaboration aren't really about technology. They're about autonomy. Who gets to choose how we work?

History often rhymes. When Halle and I realized we wrote about labor as much (or more) than we wrote about fun automation tricks, I knew I would start to see analogs to the present low-code/no-code moment in stories about past technological shifts and the history of labor relations.

This story by Brian Justie, the saga of the mechanization and automation of the U.S. Postal Service, is the purest example and is worth a full read. The analogs hit over and over again.

Delivering hards [ambiguously addressed bits of mail], no matter the cost, is a reflection of the US Post Office’s commitment to truly universal service—a radical vision of democratic communications infrastructure enshrined in the Postal Service Act of 1792. No matter the sender, the recipient, or the distance separating origin and destination, federal code stipulated that the Post Office must “bind the nation together.” As Alexis de Tocqueville put it in his 1835 treatise Democracy in America, the US mail system, unlike its European counterpart, “was organized so as to bring the same information to the door of the poor man’s cottage and to the gate of the palace.” To live up to this idealistic ethos, hards must be treated no differently than easies.

(You might know “hards” by another name: edge cases.)

In the beginning, hards and easies get roughly the same level of service and human attention. That’s how it always starts with any project or process. And that’s a wonderful aspiration.

Step two is usually pretty simple: Keep the easies moving, but throw more human energy at the hards. Already, you’re treating these two categories differently by necessity. In many projects, there isn’t enough energy or will to go further and improve the process. And that’s fine.

But when your company — or postal service, in this case — grows by 50x in the span of a few decades, that’s no longer fine.

Enter automation. Or, to be precise in the case of the Post Office, a “crash program of modernization and mechanization.”

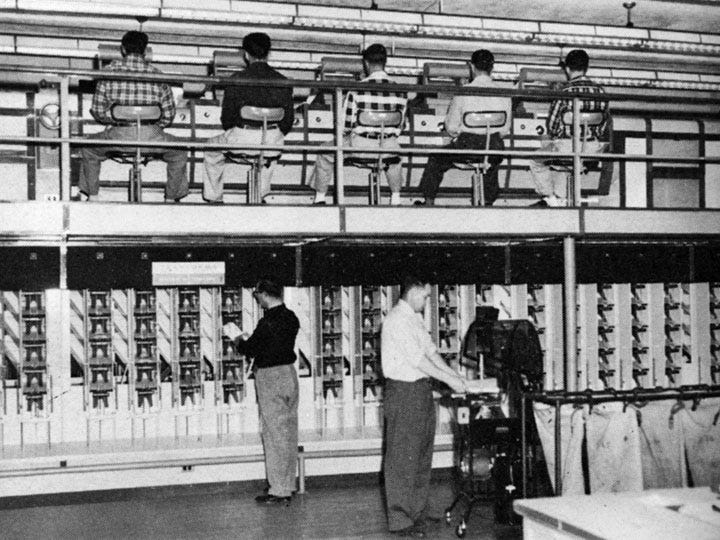

That program began in earnest in 1957 with the Transorma, a massive machine that turned the job of sorting the mail into simple data entry using specialized keyboards -- from a tactile experience into simple data entry. Crucially, the machine did not run entirely on its own -- a key difference between “mechanization” and full automation.

In the late 1960s, that tension between mechanization and automation drove a wedge between management and workers. And that conflict changed the trajectory of the postal service.

The Multi-Position Letter Sorting Machine was the successor to the Transorma. Instead of allowing the workers to advance letters through the system when they were finished with them, management pushed to make the machines self-advancing -- effectively codifying the pace of work.

In Justie’s telling, management chose predictable inefficiency over a slightly less predictable but more efficient and humane model. And by 1970, working conditions had deteriorated so much that 200,000 postal workers walked off the job in “the largest wildcat strike in American history.” Congress caved: within the year, postal workers won collective bargaining rights, including the right to have a say in the introduction of new technology in the workplace.

More than 50 years later, we can see this same story playing out. We can also see the nuances in how it plays out depending on where and how you work. If you’re an information worker or creative who can work from home, you’re likely being measured and even compensated based on value. If you work in customer service or retail, you’re likely getting paid for your time and you don’t get to choose the pace of your work.

The fight over who sets the pace of work is one of the key throughlines of labor movements across human history. Technology is more like a field we play on -- a setting that can change over time. In 1970, that field was favorable to workers. In the past few decades, the field has become more favorable to management as it became easier to rapidly fill someone’s queue with work the second they showed any signs of non-productivity.

That’s not changing. Capital will only allow productivity to go in one direction and owners have enough tools to confidently face down the threat of strikes. Now the fight is about time.

From Joe Pinsker in The Atlantic:

People who work a four-day week generally report that they’re healthier, happier, and less crunched for time; their employers report that they’re more efficient and more focused. These companies’ success points to a tantalizing possibility: that the conventional approach to work and productivity is fundamentally misguided.

“We live in a society in which overwork is treated as a badge of honor,” Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, an author and consultant who helps companies try out shorter workweeks, told me. “The idea that you can succeed as a company by working fewer hours sounds like you’re reading druidic runes or something.” But, he said, “we’ve had the productivity gains that make a four-day week possible. It’s just that they’re buried under the rubble of meetings that are too long and Slack threads that go on forever.”

It’s another article you should read in full. Two things stuck out to me that intersect with the postal service story above.

You can’t tell a worker who is paid by the hour -- likely a low-to-middle-income employee -- that their pay might get cut by 20% and expect them to take that lying down.

Even with huge companies like Microsoft and Unilever experimenting with shortened work weeks, a top-down mandate only seems likely in the event of an unprecedented depression or a revolution.

These are huge asks. They’re scary. So if this starts getting traction, I would expect some extreme pushback — not unlike what happened when we first moved from six days to five.

In 1926, the Ford Motor Company adopted the five-day week, doubling the number of American workers with that schedule.

Not all business leaders favored the change. “Any man demanding the forty hour week should be ashamed to claim citizenship in this great country,” the chairman of the board of the Philadelphia Gear Works wrote shortly after Ford rolled out its new hours. “The men of our country are becoming a race of softies and mollycoddles.”

“The men of our country are becoming a race of softies and mollycoddles” is obviously absurd rhetroic in 2021. And yet Naomi Schaefer Riley, a Resident Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, argued exactly that in a bizarre op-ed this week.

Consider how things have changed. Today, unpaid internships look better on college resumes. But years ago, my own father actually managed to put a significant dent in his college tuition by working as a waiter in the Catskills all summer. Today, even a full summer of lifeguarding or busing tables is unlikely to do more than cover a kid’s incidental expenses at a four-year school. So why bother?

Well, for one, and forgive my hypocrisy, there are valuable lessons to be learned. Some are about the feeling of independence that comes from earning a paycheck — and seeing how much the government takes away. Some are about humility. Handling other people’s money, other people’s food and other people’s children often means being at the receiving end of rudeness and anger. I’m not condoning such behavior, but there are times in life when remembering that the customer is always right will end up saving you a lot of heartache.

This attitude about low-wage jobs as irreplicable teaching moments is dangerous. On one hand, it romanticizes survival-level work. On the other hand, it reinforces a toxic narrative for those of us who do participate in knowledge work: that more output is always better. And in either case, if your job is physically overburdensome, if you’re being abused or harassed or having your wages stolen by your manager, if you’re being bullied by co-workers or customers… tough shit, it’s a rite of passage.

You can hear this same narrative as managers start telling employees to come back to the office five days a week. Messages that reek of desperation to control employees’ time and output at the expense of their health and happiness.

The wonder of this moment is finally getting to decide for ourselves to whom our time belongs.

Nia knows what’s up: